Light Music

May 7, 2012

With the Titanic centenary still resounding, now comes the 75th anniversary of the Hindenburg disaster. Did you know that it was furnished with a piano made of aluminum and pigskin?

Art and Hype

May 3, 2012

I’m frequently in conversations with musicians — composers or performers — who bemoan the subordinate role that ability and quality of output may often play in their success or obscurity. It’s not only having a industrious and cunning publicist that makes the difference; it can be just one work that catches the imagination of the media or public and propels a career.

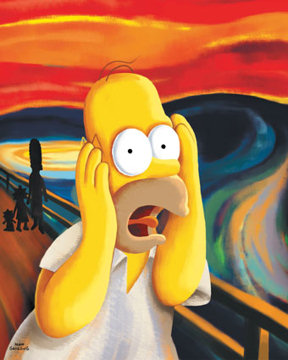

The whole subject has been on my mind since the news that The Scream by Edvard Munch sold for an astounding $120 million last night. Whatever determined that price, it was not the artistic quality of the work. As Clyde Haberman says, “If you’ve never seen a tacky facsimile of it, there’s a chance that you have also never seen a coffee mug, a T-shirt or a Macaulay Culkin poster.” If they weren’t paying for art, what were the buyers shelling out all that money for? An economist nails it: “Whatever was being bought, here, it wasn’t really art, in any pure sense. It was more the result of a century’s worth of marketing and hype.”

It’s not only in Hollywood or Washington that name-recognition rules.

The Mattila Case

April 28, 2012

Whether you admire the music or not (and I do) and whether you like her voice or not (and I do), you owe it to yourself to see Karita Mattila in The Makropulos Case at the Met. Rarely can anyone have owned that stage the way she did at tonight’s opening. There are four remaining performances.

4′ 33″

April 26, 2012

As long as I can remember, I’ve heard lots of sniggering over John Cage’s composition of that name. People often assume that it’s, at best, a joke or, at worst, an imposture. Not everyone is convinced by the composer’s explanation that, even in the most silent public space, there is going to be noise and that the truly sensitive listener should learn to be aware of all of it. If that noise is only the sounds of respiration or seat-creaking or the subway going by, it may take an exceptional person to find them rewarding.

But look at the photograph above. That‘s where the premiere of 4’33” took place in a summer night surrounded by the sounds of nature. Now can we agree that Cage may have had a point?

My Favorite Easter Organ Work

April 10, 2012

Oliver Messiaen’s “Joie et clarté des corps glorieux” (Joy and Light of the Glorious Bodies) is from his Les Corps glorieux: Sept Visions brèves de la vie des ressuscités (The Glorious Bodies: Seven Brief Visions of the Life of the Resurrected). He explained what the music portrays with a verse of scripture: “Then shall the righteous shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father.”

The entire suite was completed in August of 1939 and was his last composition before his imprisonment by the Nazis, which suffices to explain its delayed premiere. While Messiaen always spoke of the organ at La Trinité as his “laboratoire,” he gave the first public performance of this movement in a recital at Paris’s Palais de Chaillot at the end of December 1941, and the premiere of the complete suite did not take place until November of 1943, in the same hall.

Messiaen was ready with an answer to those who often bitterly criticized him for the apparently profane nature of his music. It was felt to be over-dramatic, too sensuous, impure. In a conversation with Antoine Goléa the composer defended himself vehemently:

Those people who reproach me do not know the dogma and know even less about the sacred books… They expect from me a charming, sweet music, vaguely mystical and above all soporific. As an organist I have been able to note the set texts for the liturgy… Do you think that psalms, for example, speak of sweet and sugary things? A psalm groans, howls, bellows, beseeches, exults, and rejoices in turn.

This performance, though on an instrument that is not at all of the same character as that of Messiaen, is a successful one:

Triduum Sacrum

April 7, 2012

Like many others, I’ve been completely consumed with doing music for the great liturgies of the Three Days. Pictured above, from this morning, is the third Tenebrae liturgy, at the Church of Notre Dame here in the city. Tonight comes the climax, with the Easter Vigil in the Holy Night.

Passionate Group Improvisation

April 4, 2012

The main takeaway I get from this performance is that this quite effective presentation of the Passion is musically as good as the compositions of quite a few highly popular or award-winning “classical” composers. If a choir of good professional singers can improvise this kind of music, what does it say about the guys who are lauded for putting on long faces and composing it?